Game Theory And The Cold War Museum

- Cold War Museum Website

- Game Theory Cold War

- Game Theory And The Humanities

- Cold War Museum Ohio

- Game Theory And The Evolution Of Signaling

Game Theory and Nuclear War While most of the 65,000 active nuclear weapons from 1985 are gone, there still remain over 4,000 active nuclear warheads. Yet, since WWII, not a single nuclear weapon has been used against another nation. Would have political advantage in other fields of the Cold War (e.g. The problem of Berlin). Bertrand Russel (1953) compared the Cold War politics to the chicken game, known from game theory. Jacek Rothert Cold War and Game Theory. Thomas Schelling (1921-2016) Thomas Schelling was one of the greatest game theorists, Nobel Laureate in 2005, and influential advisor for several U.S. During the Cold War, he produced several consequential ideas. On the one hand, he supported the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) between the USA and the USSR.

Disclaimer: This work has been submitted by a student. This is not an example of the work produced by our Essay Writing Service. You can view samples of our professional work here.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of UK Essays.

Since the beginning of human life, two main reasons for the war amongst men has been ones survival, or the urge to gain territories. Recently, our rapid advance in the field of science and technology has resulted in greatly improved tools of warfare. This has made these wars more and more deadly. The development of better technology has brought a revolution in the field of military warfare and also in our personal lives.

2. The word ‘deterrence’, variously described as ‘avoidance’, ‘prevention’ and ‘preclusion’ is as old as the origin of mankind. It evolved along with the capacity of the human beings to inflict pain and to anticipate the other person’s capability to inflict such pain. But, this term – ‘deterrence’ is accredited to Bernard Brodie through his book ‘The Absolute Weapon’, in which he stated hat the main purpose of military was not to win wars, but to prevent it. The holocaust of World War II as well as the conventional forces of Soviet Unions presented a credible threat to the existence of Western Europe. The political and social cost of attempting to defend Western Europe with conventional forces being prohibitive led to the adoption of nuclear deterrence strategy by the USA.

3. The unstable peace and chaos of the post cold war era are caused by innumerable instabilities. The causes include increasing poverty, starvation, widespread disease and lack of political and socio-economic justice. The consequences are seen in such forms as social violence, criminal anarchy, refugee flows, illegal drug trafficking, organized crime, extreme nationalism, religious fundamentalism, insurgency, ethnic cleansing and environmental devastation. These conditions tend to be exploited by militant reformers, civil, military bureaucrats, terrorists, insurgents, warlords and rogue states for their narrow purposes.

4. Game Theory and its Application. Game theory is described as a mathematical theory of decision making in a conflict situation. It provides a precise way to describe the key elements in situations where there are many actors, with different goal resources and information, each with only partial control over the factors determining the outcome. How the rules of game theory can best be applied to the aspect of nuclear deterrence is the challenge for this dissertation.

Statement of the Problem

5. The most essential issue which the world faces today is thus the search for a security system which shall replace the nuclear deterrence strategy of the cold war era. Does the global security lie in replacing nuclear weapons with more precise and highly lethal conventional weapons in the matrix of deterrence logic? Have nuclear weapons become un-useable and thus irrelevant? Are their any other emerging strategies? This dissertation propounds the hypothesis that the present world matrix will not permit the nuclear war, therefore will India’s nuclear deterrence loose its relevance in the 21st Century and the role of conventional forces and weapons in the overall deterrence framework shall continue to grow.

Aim

6. The dissertation attempts to analyse the relevance of India’s nuclear deterrence vis a vis developing a strong conventional deterrence in the Indian sub continent and application of Game theory as relevant to nuclear deterrence.

Hypothesis

7. Possession of Nuclear Weapons is likely to provide a deterrence to India against potential adversaries.

Scope

8. The hypothesis proposed above will be discussed under the following heads:-

(a) Evolution of deterrence doctrine.

Flaws in deterrence doctrine.

Issue of future conflicts and nature of future wars.

(d) Role of conventional forces.

(e) Deterrence in Sino-Indo-Pak context.

(f) Application of Game theory in Nuclear Deterrence

Methodology

9. The process of data collection commenced with the scanning of literature on the subject and research papers / thesis by the premier Service institutions like College of Defence Management, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis and United Service Institution of India. Websites were accessed for the Concepts and Relevance of Nuclear Deterrence since its evolution during the World War II and changes it has undergone over the history coming into the 21st Century. India’s draft Nuclear Doctrine and that of the nuclear weapon states like USA, China and also Pakistan which were available in the open domain were examined for relevant inputs. The literature on Game theory and its applications has also been collected for research and relevant analysis.

Chapter 1

10. Introduction and Methodology.

Chapter 2 : Evolution of ‘Deterrence’.

11. Deterrence is a relation between parties (individual, institutions, or groups) wherein one party (explicitly or implicitly) indicates benchmarks of behaviour and expresses a commitment to use force, if the second party’s behaviour does not match to these enunciated standards. The object of deterrence is to persuade an adversary that the cost of non-adherence to the laid down norms will far outweigh the benefits. Deterrence is an important factor in international diplomacy. There are many acts of deterring that rightly are considered morally acceptable; including making threats of lethal action. In simple words, as long as a State can anticipate the pain that can be inflicted on it by another State, and therefore in anticipation of the pain, it modifies its conduct, that is deterrence.

12. The chapter shall explain the meaning of ‘Deterrence’ before the nuclear age and in the nuclear age and a brief study of deterrence in cases of asymmetry and in cases of near symmetry. It will also analyse the meaning of perception, since in ensuring deterrence and removing risks it should be clear that a misperception can occur either in International relations or, more importantly, in deterrence theory. It also explains the types of misperceptions that can cause deterrence to fail. Subsequently some of the deterrence related terminologies and deterrent philosophies afloat today are also elaborated. From nuclear deterrence philosophies have evolved a number of nuclear targeting philosophies and they too are explained in detail.

Chapter 3 : Deterrence in Sino-Indo-Pak Context and Role of Conventional Forces.

13. The nations of South Asia share geographical contiguity and historical, cultural and religious ties. However, the region has a long history of war and insurgency, civil strife and ethnic rivalry. Poverty and illiteracy, an increasing gap between rich and poor, violence between castes and creeds are posing threats to state and society. Minority discontent often explodes into armed insurgency. Endemic poverty is another common feature throughout South Asia. India’s security environment is not a self-contained region. The power asymmetry and the geographical Indo-centricity of the region make it a brittle strategic environment. Our territorial disputes with many of our neighbours complicate the situation. The strategic environment in South Asia has been remarkably conflict laden, characterised by wars or hostile relations between each other and especially between India and her neighbours.

14. India is in the unenviable position of having two nuclear armed neighbours with both of whom it has fought wars in the past. China and Pakistan are the two important players who affect India’s security environment. The nuclear stands of these three nations are directly related to their mutual threat perceptions and security concerns. To understand and analyse India’s nuclear environment in the future, it would thus be appropriate to analyse nuclear threat from China and Pakistan. This would in turn dictate the thrust of India’s nuclear policy. This part shall include:-

(a) India’s Nuclear Environment.

(b) Threat perceptions of India, China and Pakistan.

(c) Nuclear threat to India from China and Pakistan

Chapter 4 : Game Theory Model for Selecting Optimal COA

15. This Chapter encompasses:-

Evolution of procedure for preparation of payoff matrix including a brief examination of ten step procedure for preparation of a payoff matrix suggested by Lt Col Gregory L. Cantwell, United States Army.

Quantification of Pay Offs with Key Decision Factors (Seven Step Method).

Case Study examination of seven step method for preparation of payoff matrix.

16. A Seven Step Procedure as given below has been evolved for aiding selection of CsOA amongst competing CsOA by Decision makers:-

(a) Step 1. List out own and enemy CsOA based on mission analysis of the decision situation.

(b) Step 2. Selection of KDFs by Decision Maker.

(c) Step 3. Establish inter se priorities to KDFs by allocation of AWC by Decision Maker assisted by experts / advisers employing AHP technique.

Step 4. Examination of own CsOA actions for the KDF with respect to enemy CsOA. Allocate values on scale of one to five. Decision Maker can seek inputs from experts / advisers and also allocate values as per his judgment.

Step 5. Prepare a Synthesized Matrix of AWC and Values generated at Step 4.

Step 6. Translate values from Step 5 in to two person ZSG matrix of payoffs.

Step 7. Solve the two person ZSG.

Chapter 5 : Hypothesis Testing

17. Hypothesis has been validated with the help of case study of OP PARAKRAM. Competing CsOA for India and Pakistan were listed in questionnaire. Participants of HDMC – 7 were asked to determine the payoffs of various outcomes from interaction of Indian and Pakistani CsOA. AWC of KDF has been obtained from experts (three members from Department of Strategic Management). Case was solved with Seven Step Process.

Chapter 6 – Conclusion

18. This study seeks to extrapolate Game Theory precepts in the domain of military decision making process in the Indian Armed Forces. The study has attempted to address one of the key challenges of building a pay off matrix for competing CsOA. This concluding chapter summarizes the research and the final outcome as it emerged from the arguments presented in the research paper / survey of participants. Examination of nature of Game Theory features which favour its application and key challenges in its application have been included in the chapter besides recommendations on areas for further study and research.The nations of South Asia share geographical contiguity and historical, cultural and religious ties. However, the region has a long history of war and insurgency, civil strife and ethnic rivalry. Poverty and illiteracy, an increasing gap between rich and poor, violence between castes and creeds are posing threats to state and society. Minority discontent often explodes into armed insurgency. Endemic poverty is another common feature throughout South Asia. India’s security environment is not a self-contained region. The power asymmetry and the geographical Indo-centricity of the region make it a brittle strategic environment. Our territorial disputes with many of our neighbours complicate the situation. The strategic environment in South Asia has been remarkably conflict laden, characterised by wars or hostile relations between each other and especially between India and her neighbours.

19. Is practicing nuclear deterrence prudentially preferable to not practicing it? Does prudence in the end counsel maintaining or abandoning nuclear deterrence? This is the central question in any examination of the fundamentals of nuclear weapons policy. The relevance of nuclear deterrence in the Indian context and to suggest if any change is required in its present nuclear policy is but an exercise in the choice of ends and means on the part of the nation state and being a dynamic process will keep changing as per existing scenario. My dissertation will just be a process of putting forward a few known facts and their relevance, to come to, in my opinion, a viable nuclear option.

“Autonomy of decision-making in the developmental process and in strategic matters is an inalienable democratic right of the Indian people. India will strenuously guard this right in a world where nuclear weapons for a select few are sought to be legitimised for an indefinite future.”

“India should remain in a position to retaliate if nuclear weapons are used against us.”

Brajesh Mishra

(Former National

Security Adviser)

INTRODUCTION

Background and Justification for the Study

War, is presupposed and predetermined by many psychological theories, as being innate to human nature. Hence, there is little hope of ever escaping it. Psychologists argue that human temperament allows wars to occur only when mentally unbalanced people are in control of a nation. They are of the opinion that leaders who seek war like – Napoleon, Hitler, Osama bin Laden, Saddam Hussein and Stalin were mentally abnormal. Yet they fail to explain the thousands of free and sane people who wage wars at their behest. Some psychologists believe such leaders are the product of the anger and madness repressed in modern societies. As people elect and support such leaders, suggestions have been made that very few people are sane and that modern society is an unhealthy one [1] .

Game Theory (or more appropriately Games of Strategy) which entails interactive decision-making is relatively new field of science having come to fore only in later part of 20th Century. However, it has found vast and varied application in diverse fields such as economy, politics and social sciences. Its application in military decision making process and in examination of politico – military strategic issues has been at low ebb, more so in the Indian context. Decision making is one of the most important roles of military commanders at all levels and they often face decision dilemmas to choose from competing CsOA. More often than not their choices in such situations are based on intuitive quality judgements based on experiences of individual commanders.

Game Theory is the science of interactive decision-making. Decision making is one of the most important facets of military commanders at all levels as decisions are essentially the means by which a Commander translates his vision of end state into action. The process of decision making entails, knowing if to decide, then when and what to decide [2] .

The First World War, its resulting ideologies like Communism, Fascism, and Nazism, and the Second World War, saw such devastation that the thought of war became taboo. This resulted in the Treaty of Versailles, and the formation of the League of Nations as an attempt to form deterrence against such carnage. Though these proved unsuccessful, they did give rise to an idea.

The word ‘deterrence’, variously described as ‘avoidance’, ‘prevention’ and ‘preclusion’ is as old as the origin of mankind. It evolved along with the capacity of the human beings to inflict pain and to anticipate the other person’s capability to inflict such pain. But, this term – ‘deterrence’ is accredited to Bernard Brodie through his book ‘The Absolute Weapon’, in which he stated that the main purpose of military was not to win wars, but to prevent it. The holocaust of World War II as well as the conventional forces of Soviet Unions presented a credible threat to the existence of Western Europe. The political and social cost of attempting to defend Western Europe with conventional forces being prohibitive led to the adoption of nuclear deterrence strategy by the USA [3] .

Presidents Reagan and Gorbachev announced together in November 1985 at Vienna, that a nuclear war could not be won and hence must never be fought. Subsequently both the USA and USSR initiated substantial measures to reduce the possibilities of war in other areas. But this has not eliminated war elsewhere.

The unstable peace and chaos of the post-cold war era are caused by innumerable instabilities. The causes include increasing poverty, starvation, widespread disease and lack of political and socio-economic justice. The consequences are seen in such forms as social violence, criminal anarchy, refugee flows, illegal drug trafficking, organized crime, extreme nationalism, religious fundamentalism, insurgency, ethnic cleansing and environmental devastation [4] . These conditions tend to be exploited by militant reformers, civil, military bureaucrats, terrorists, insurgents, warlords and rogue states for their narrow purposes.

Statement of the Problem

The most essential issue which the world faces today is thus the search for a security system which shall replace the nuclear deterrence strategy of the cold war era. Does the global security lie in replacing nuclear weapons with more precise and highly lethal conventional weapons in the matrix of deterrence logic? Have nuclear weapons become unusable and thus irrelevant? Are their any other emerging strategies? This dissertation propounds the hypothesis that the present world matrix will not permit the nuclear war, therefore will India’s nuclear deterrence loose its relevance and the role of conventional forces and weapons in the overall deterrence framework continue to grow.

Aim

The research attempts to analyse the relevance of India’s nuclear deterrence vis a vis developing a strong conventional deterrence in the Indian sub continent. This shall be attempted by exploring application of Game Theory for nuclear decision making with focus on its usefulness in facilitating selection of optimal COA by decision makers.

Hypothesis

Possession of Nuclear Weapons is likely to provide a deterrence to India against potential adversaries.

Scope

The hypothesis proposed above will be discussed under the following heads:

Evolution of deterrence doctrine and inherent flaws.

Issue of future conflicts and nature of future wars.

Role of conventional forces.

Deterrence in Sino-Indo-Pak context.

Hypothesis testing using Game Theory.

Methodology

The process of data collection commenced with the scanning of literature on the subject and research papers / thesis by the premier Service institutions like College of Defence Management, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis and United Service Institution of India. Websites were accessed for the Concepts and Relevance of Nuclear Deterrence since its evolution during the World War II and changes it has undergone over the history coming into the 21st Century. India’s draft Nuclear Doctrine and that of the nuclear weapon states like

USA, China and also Pakistan which were available in the open domain were examined for relevant inputs. Advise and valuable inputs from the mentor DS and guest speakers visiting the college have also been obtained on the subject. A survey of participants has been undertaken to gauge awareness, aptitude and inclination of officers in adopting Game Theory in decision making.

Case Study Method. A case study approach has been adopted to place the subject in perspective and keep the arguments interesting, thus, avoiding monotonous reading. A Seven Step process envisaged for application of Game Theory has been validated with a Case Study based on a conflict situation between India and Pakistan.

Hypothesis Validation. Hypothesis has been validated with the help of a Questionnaire. A real life case of OP PARAKRAM situation was painted to the respondents who were asked to determine the payoffs of various outcomes from Indian and Pakistani CsOA. Thereafter, the problem was analysed with ‘Seven Step Process’.

Preview

The research paper will be covered in the chapters as shown below:-

Chapter- 2. Evolution of Deterrence Doctrine.

Chapter – 3. Deterrence in Sino-Indo-Pak Context and Role of Conventional Forces.

Chapter- 4. Game Theory Model for Selecting Optimal COA.

Chapter -5. Hypothesis Testing.

Conclusion.

CHAPTER 2

EVOLUTION OF DETERRENCE DOCTRINE

Deterrence

Deterrence aims to prevent an enemy power taking the decision to use armed force; put in more general terms this means compelling him, when faced with a given situation, to act or react in the light of existence of a set of dispositions which constitute an effective threat. The result which is desired to be achieved is therefore a psychological one and is sought by means of a threat [5] .

This psychological result is the product of combined effect of a calculation of risk incurred compared to the issue at stake and of the fear engendered by the risks and uncertainties of war. The fear springs from complex psychological factors of a political, social and moral nature. These factors are closely linked to the material calculation but, on occasions, may be independent of it [6] .

First Official Mention of Theory of Deterrence. The idea that atomic bombs could be used in a strategy of deterring an attack was broached by the Joint Chiefs of Staff of USA in June 1946. This declassified document reads,” It is remotely conceivable that the atomic bomb provides its own deterrent – in that fear of retaliation by atomic bombs against a violator who uses them will make the potential violator pause and consider before he decides to go ahead. “

Strategy of City Bursting (1947). This strategy was evolved during the Truman administration in 1947. It involved deterrence of attack on US vital interests by drastic threat of atomic destruction. It was supported by plans to use Strategic Air Command bombers to destroy largest soviet urban-industrial centers. Major advantage of this strategy was that it played to US strength and Soviet weakness. The Soviets knew that they could not be prevented from seizing all of Europe, but they also knew that mother Russia could be destroyed in bargain. It thus offered relatively cheap way (politically and economically) to maintain peace and freedom of Western Europe. A national policy of deterrence was formally approved by the National Security Council of USA on November 1948.

Berlin Crisis. During the Berlin crisis in 1948 USA dispatched its B-20 and B-29 squadrons to Germany and UK. Although US government press release described the B-29 flown overseas as atomic capable, they were actually not modified to carry the atomic bomb. Although this was a military ruse, it established the practice of nuclear deterrence in advance of its theoretical enunciation by US war planners [7] .

Extended Deterrence [8] (1948). This involved the use of nuclear power by US to protect non nuclear allies. This was developed to protect Western Europe against Soviet Union. The final victory of communists in the Chinese civil war, and the first atomic explosion by the Soviet Union made America more anxious about their relative security.

Strategy of Massive Retaliation [9] (1953-54). This strategy implied deterrence by threat to launch all out nuclear retaliation. US experience of Korean War was also responsible for bringing about this change.

Strategy of Graduated Deterrence [10] (Post 1954). The local aggression was to be deterred by making it sufficiently costly to the initiator so as not to be worthwhile. It aimed to develop a form of limited nuclear war that would deter future Korean sized offensives but, it never became an official US doctrine.

Strategy of Flexible Response [11] (Early Sixties). US wanting more options in conflict, reduced reliance on nuclear weapons. The US administration also accelerated spending on achieving second strike capability. The USA also adopted a Triad strategic force. In 1980 US deployed the fourth leg of the triad –

the cruise missile.

City Avoidance [12] (1961-62). Adversary was to be deterred by threatened destruction of his military forces, not his civilian population. This gave US more options in conflict, for example US could respond to soviet nuclear attack in Europe without necessarily initiating mutual exchange of attacks against cities. It was said to provide more credible threat because USSR was seen as placing higher value on its military forces.

Assured Destruction [13] (1964). Deterrence rests on retaining capability to inflict unacceptable damage on adversary even after absorbing surprise nuclear attack. The growing US missile superiority allowed US planners to establish quantitative criteria for determining size, characteristics and effectiveness of US nuclear forces.

Mutually Assured Destruction [14] (Mid Sixties). Deterrence now rests on ability of both sides to destroy each other even after they have been attacked. This concept was economical as US did not have to strive for nuclear superiority. It provided incentive for seeking arms limitations agreements.

Sufficiency [15] (1969). To destroy USSR and China, Nixon administration inherited much larger nuclear force than needed. Policy provided rationale for not having constantly to increase nuclear power.

Finite Deterrence (Minimum Deterrence-1970). Deterrence to be achieved by maintaining only a minimum level of nuclear force, which would inflict “unacceptable damage.”

Flexible Targeting [16] (1970-74). Deterrence to be achieved by developing wider range of strategic options against military targets. This

provided ways in which US surplus of warheads could be put to `good’ use.

Countervailing Strategy [17] (Late Seventies). This strategy was adopted in the hope to convince Soviets that no use of nuclear weapons and at any stage of conflict could lead to victory. New policy was seen as more ‘moral’ (people not targeted directly).

Horizontal Escalation [18] (1983). Soviet attacks against vulnerable US military interests to be deterred by threatening to retaliate against equally important and vulnerable soviet interests.

Simultaneity [19] (Late Eighties to Nineties). US had fear that in major conflict with soviets, it might not have time to shift forces from one region to another. The capability to fight on all fronts could only deter Soviet aggression.

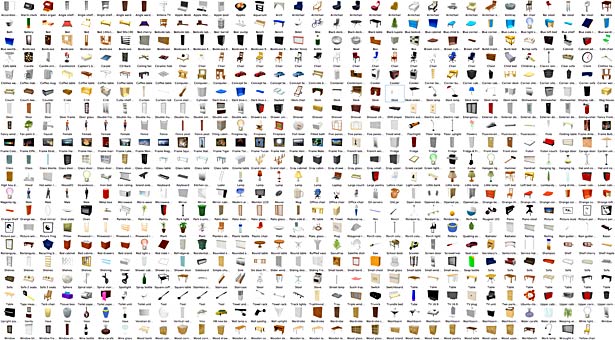

Free 3D models created by contributors The proposes more than 1100 additional 3D models created by contributors and supported in the of Sweet Home 3D. A SH3F file groups some models with their description, and can be easily installed by double-clicking on it or by choosing Furniture > Import furniture library menu item in Sweet Home 3D. Libraries of 3D models Sweet Home 3D lets you also import libraries of 3D models stored in SH3F files. The following ZIP files contains a SH3F file you can import in Sweet Home 3D.

Emerging Strategic Environment. With the dismantling of USSR, USA emerged as the only superpower. The campaign in Iraq followed by Kosovo and subsequently post Sep 11 events in Afghanistan demonstrated the awesome power of the USA. Its global strategy from Prevent, Deter and Defeat has now shifted to that of neo-imperialism wherein USA abrogates to itself the global role of setting standards, determining threats, using force and meting out justice. Proponents of nuclear deterrence argue that it remains a recessed feature that continues to impart stability in relations among China, Russia and the West.

Flaws In Deterrence Doctrine

General. Nuclear deterrence doctrine is the main stated reason for proliferation of nuclear weapons. It suffers from doctrinal flaws, vague notions, some questionable assumptions and diverting scarce resources away from development. Misgivings about it stem from doubts that balance of terror actually served to deter than in the manner often assumed by proponents of nuclear deterrence.

Deterrence and Defence. Nuclear deterrence strategy replaced the conventional force deterrence prior to the invention of nuclear weapons. This was done without giving adequate thought to the fact that the conventional and the nuclear situations are fundamentally dissimilar. In the past and even today, conventional weapons were amassed to deter an aggression before actual war and they were used to defend against that aggression if deterrence failed. Today the practical utility of nuclear weapons which can wreak havoc at an unparalleled state is highly questionable should deterrence fail. Conventional forces are still required to defend.

Rational Actor [20] . The second serious problem with nuclear deterrence has to do with the notion of rationality. Considerable evidence has been accumulated which suggests that the rational actor model does not prevail across the board in international politics. High level decision makers frequently do not act rationally, particularly under the stressful conditions inherent in crisis situations. Even if decision makers were to be rational, nothing can be said about the accuracy of information employed in rational calculations.

Problem of Credibility. Proponents of nuclear deterrence strategies argue that the threat must be credible to work in the way it should. Henry Kissinger stated the case even more strongly in 1979 when he said,” It is absurd to base the strategy of the West on the credibility of the threat of mutual suicide”.

Notions of Sufficiency. Development of nuclear weapons is often justified by invoking the strategy of deterrence, yet no strategic thinker can say with any degree of certainty as to how many and of what kinds of weapons are sufficient for deterrence. The result is an upward spiral of the arms race which was frequently justified on the need to continue to deter the other side.

Uni-Dimensional Character. The nuclear deterrence theory relies on instilling fear in an opponent to change his behavior. So, it disregards all other factors which may influence a foe’s behavior.

Inherent Danger. Policy of deterrence relies on threat and people can react differently to threats. Ironically the very weapons which intended to deter war could well accelera

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

|

|

|

Deterrence theory is the idea that an inferior force, by virtue of the destructive power of the force's weapons, could deter a more powerful adversary, provided that this force could be protected against destruction by a surprise attack. This doctrine gained increased prominence as a military strategy during the Cold War with regard to the use of nuclear weapons and is related to, but distinct from, the concept of Mutual assured destruction, which models the preventative nature of full-scale nuclear attack that would devastate both parties in a nuclear war. Deterrence is a strategy intended to dissuade an adversary from taking an action not yet started by means of threat of reprisal,[1] or to prevent them from doing something that another state desires. The strategy is based on the psychologicalconcept of the same name. A credible nuclear deterrent, Bernard Brodie wrote in 1959, must be always at the ready, yet never used.[2][a]

In Thomas Schelling's (1966) classic work on deterrence, the concept that military strategy can no longer be defined as the science of military victory is presented. Instead, it is argued that military strategy was now equally, if not more, the art of coercion, of intimidation and deterrence.[3] Schelling says the capacity to harm another state is now used as a motivating factor for other states to avoid it and influence another state's behavior. To be coercive or deter another state, violence must be anticipated and avoidable by accommodation. It can therefore be summarized that the use of the power to hurt as bargaining power is the foundation of deterrence theory, and is most successful when it is held in reserve.[3]

In 2004 Frank C. Zagare made the case that deterrence theory is logically inconsistent, not empirically accurate, and that it is deficient as a theory. In place of classical deterrence, rational choice scholars have argued for perfect deterrence, which assumes that states may vary in their internal characteristics and especially in the credibility of their threats of retaliation.[4]

In a January 2007 article in the Wall Street Journal, veteran cold-war policy makers Henry Kissinger, Bill Perry, George Shultz, and Sam Nunn reversed their previous position and asserted that far from making the world safer, nuclear weapons had become a source of extreme risk.[5] Their rationale and conclusion was not based on the old world with only a few nuclear players, but on the instability in many states possessing the technologies and the lack of wherewithal to properly maintain and upgrade existing weapons in many states:

The risk of accidents, misjudgments or unauthorised launches, they argued, was growing more acute in a world of rivalries between relatively new nuclear states that lacked the security safeguards developed over many years by America and the Soviet Union. The emergence of pariah states, such as North Korea (possibly soon to be joined by Iran), armed with nuclear weapons was adding to the fear as was the declared ambition of terrorists to steal, buy or build a nuclear device.[5]

According to The Economist, 'Senior European statesmen and women' called for further action in 2010 in addressing problems of nuclear weapons proliferation. They said: 'Nuclear deterrence is a far less persuasive strategic response to a world of potential regional nuclear arms races and nuclear terrorism than it was to the cold war'.[6]

- 1Concept

- 2Rational deterrence theory

- 4Stages of the US policy of deterrence

Concept[edit]

The use of military threats as a means to deter international crises and war has been a central topic of international security research for at least 200 years.[7] Research has predominantly focused on the theory of rational deterrence to analyze the conditions under which conventional deterrence is likely to succeed or fail. Alternative theories however have challenged the rational deterrence theory and have focused on organizational theory and cognitive psychology.[8]

The concept of deterrence can be defined as the use of threats by one party to convince another party to refrain from initiating some course of action.[9] A threat serves as a deterrent to the extent that it convinces its target not to carry out the intended action because of the costs and losses that target would incur. In international security, a policy of deterrence generally refers to threats of military retaliation directed by the leaders of one state to the leaders of another in an attempt to prevent the other state from resorting to the threat of use of military force in pursuit of its foreign policy goals.

As outlined by Huth,[9] a policy of deterrence can fit into two broad categories being (i) preventing an armed attack against a state's own territory (known as direct deterrence); or (ii) preventing an armed attack against another state (known as extended deterrence). Situations of direct deterrence often occur when there is a territorial dispute between neighboring states in which major powers like the United States do not directly intervene. On the other hand, situations of extended deterrence often occur when a great power becomes involved. It is the latter that has generated the majority of interest in academic literature. Building on these two broad categories, Huth goes on to outline that deterrence policies may be implemented in response to a pressing short-term threat (known as immediate deterrence) or as strategy to prevent a military conflict or short term threat from arising (known as general deterrence).

A successful deterrence policy must be considered in not only military terms, but also in political terms; specifically International Relations (IR), foreign policy and diplomacy. In military terms, deterrence success refers to preventing state leaders from issuing military threats and actions that escalate peacetime diplomatic and military cooperation into a crisis or militarized confrontation which threatens armed conflict and possibly war. The prevention of crises of wars however is not the only aim of deterrence. In addition, defending states must be able to resist the political and military demands of a potential attacking nation. If armed conflict is avoided at the price of diplomatic concessions to the maximum demands of the potential attacking nation under the threat of war, then it cannot be claimed that deterrence has succeeded.

Furthermore, as Jentleson et al.[10] argue, two key sets of factors for successful deterrence are important being (i) a defending state strategy that firstly balances credible coercion and deft diplomacy consistent with the three criteria of proportionality, reciprocity, and coercive credibility, and secondly minimizes international and domestic constraints; and (ii) the extent of an attacking state's vulnerability as shaped by its domestic political and economic conditions. In broad terms, a state wishing to implement a strategy of deterrence is most likely to succeed if the costs of non-compliance it can impose on, and the benefits of compliance it can offer to, another state are greater than the benefits of noncompliance and the costs of compliance.

Deterrence theory holds that nuclear weapons are intended to deter other states from attacking with their nuclear weapons, through the promise of retaliation and possibly mutually assured destruction (MAD). Nuclear deterrence can also be applied to an attack by conventional forces; for example, the doctrine of massive retaliation threatened to launch US nuclear weapons in response to Soviet attacks.

A successful nuclear deterrent requires that a country preserve its ability to retaliate, either by responding before its own weapons are destroyed or by ensuring a second strike capability. A nuclear deterrent is sometimes composed of a nuclear triad, as in the case of the nuclear weapons owned by the United States, Russia, the People's Republic of China and India. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom and France, have only sea- and air-based nuclear weapons.

Proportionality[edit]

Jentleson et al. provide further detail in relation to these factors.[10] Firstly, proportionality refers to the relationship between the defending state's scope and nature of the objectives being pursued, and the instruments available for use to pursue this. The more the defending state demands of another state, the higher that state's costs of compliance and the greater need for the defending state's strategy to increase the costs of noncompliance and the benefits of compliance. This is a challenge, as deterrence is, by definition, a strategy of limited means. George (1991) goes on to explain that deterrence may, but is not required to, go beyond threats to the actual use of military force; but if force is actually used, it must be limited and fall short of full-scale use or war otherwise it fails.[11] The main source of disproportionality is an objective that goes beyond policy change to regime change. This has been seen in the cases of Libya, Iraq, and North Korea where defending states have sought to change the leadership of a state in addition to policy changes relating primarily to their nuclear weapons programs.

Reciprocity[edit]

Secondly, Jentleson et al.[10] outline that reciprocity involves an explicit understanding of linkage between the defending state's carrots and the attacking state's concessions. The balance lies neither in offering too little too late or for too much in return, not offering too much too soon or for too little return.

Coercive credibility[edit]

Finally, coercive credibility requires that, in addition to calculations about costs and benefits of cooperation, the defending state convincingly conveys to the attacking state that non-cooperation has consequences. Threats, uses of force, and other coercive instruments such as economic sanctions must be sufficiently credible to raise the attacking state's perceived costs of noncompliance. A defending state having a superior military capability or economic strength in itself is not enough to ensure credibility. Indeed, all three elements of a balanced deterrence strategy are more likely to be achieved if other major international actors like the United Nations or NATO are supportive and if opposition within the defending state's domestic politics is limited.

The other important consideration outlined by Jentleson et al.[10] that must be taken into consideration is the domestic political and economic conditions within the attacking state affecting its vulnerability to deterrence policies, and the attacking state's ability to compensate unfavourable power balances. The first factor is whether internal political support and regime security are better served by defiance, or if there are domestic political gains to be made from improving relations with the defending state. The second factor is an economic calculation of the costs that military force, sanctions, and other coercive instruments can impose, and the benefits that trade and other economic incentives may carry. This in part is a function of the strength and flexibility of the attacking state's domestic economy and its capacity to absorb or counter the costs being imposed. The third factor is the role of elites and other key domestic political figures within the attacking state. To the extent these actors' interests are threatened with the defending state's demands, they act to prevent or block the defending state's demands.

Rational deterrence theory[edit]

The predominant approach to theorizing about deterrence has entailed the use of rational choice and game-theoretic models of decision making (see game theory). Deterrence theorists have consistently argued that deterrence success is more likely if a defending state's deterrent threat is credible to an attacking state. Huth[9] outlines that a threat is considered credible if the defending state possesses both the military capabilities to inflict substantial costs on an attacking state in an armed conflict, and if the attacking state believes that the defending state is resolved to use its available military forces. Huth[9] goes on to explain the four key factors for consideration under rational deterrence theory being (i) the military balance; (ii) signaling and bargaining power; (iii) reputations for resolve; and (iv) interests at stake.

The military balance[edit]

Deterrence is often directed against state leaders who have specific territorial goals that they seek to attain either by seizing disputed territory in a limited military attack or by occupying disputed territory after the decisive defeat of the adversary's armed forces. In either case, the strategic orientation of potential attacking states is generally short term and driven by concerns about military cost and effectiveness. For successful deterrence, defending states need the military capacity to respond quickly and in strength to a range of contingencies. Where deterrence often fails is when either a defending state or an attacking state under or overestimate the others' ability to undertake a particular course of action.

Signaling and bargaining power[edit]

The central problem for a state that seeks to communicate a credible deterrent threat through diplomatic or military actions is that all defending states have an incentive to act as if they are determined to resist an attack, in the hope that the attacking state will back away from military conflict with a seemingly resolved adversary. If all defending states have such incentives, then potential attacking states may discount statements made by defending states along with any movement of military forces as merely bluffs. In this regards, rational deterrence theorists have argued that costly signals are required to communicate the credibility of a defending state's resolve. Costly signals are those actions and statements that clearly increase the risk of a military conflict and also increase the costs of backing down from a deterrent threat. States that are bluffing are unwilling to cross a certain threshold of threat and military action for fear of committing themselves to an armed conflict.

Reputations for resolve[edit]

There are three different arguments that have been developed in relation to the role of reputations in influencing deterrence outcomes. The first argument focuses on a defending state's past behaviour in international disputes and crises, which creates strong beliefs in a potential attacking state about the defending state's expected behaviour in future conflicts. The credibilities of a defending state's policies are arguably linked over time, and reputations for resolve have a powerful causal impact on an attacking state's decision whether to challenge either general or immediate deterrence. The second approach argues that reputations have a limited impact on deterrence outcomes because the credibility of deterrence is heavily determined by the specific configuration of military capabilities, interests at stake, and political constraints faced by a defending state in a given situation of attempted deterrence. The argument of this school of thought is that potential attacking states are not likely to draw strong inferences about a defending states resolve from prior conflicts because potential attacking states do not believe that a defending state's past behaviour is a reliable predictor of future behaviour. The third approach is a middle ground between the first two approaches. It argues that potential attacking states are likely to draw reputational inferences about resolve from the past behaviour of defending states only under certain conditions. The insight is the expectation that decision makers will use only certain types of information when drawing inferences about reputations, and an attacking state updates and revises its beliefs when the unanticipated behaviour of a defending state cannot be explained by case-specific variables.An example both shows that the problem extends to the perception of the third parties as well as main adversaries and underlies the way in which attempts at deterrence can not only fail but backfire if the assumptions about the others' perceptions are incorrect.[12]

Interests at stake[edit]

Although costly signaling and bargaining power are more well established arguments in rational deterrence theory, the interests of defending states are not as well known, and attacking states may look beyond the short term bargaining tactics of a defending state and seek to determine what interests are at stake for the defending state that would justify the risks of a military conflict. The argument here is that defending states that have greater interests at stake in a dispute are more resolved to use force and be more willing to endure military losses to secure those interests. Even less well established arguments are the specific interests that are more salient to state leaders such as military interests versus economic interests.

Furthermore, Huth[9] argues that both supporters and critics of rational deterrence theory agree that an unfavourable assessment of the domestic and international status quo by state leaders can undermine or severely test the success of deterrence. In a rational choice approach, if the expected utility of not using force is reduced by a declining status quo position, then deterrence failure is more likely, since the alternative option of using force becomes relatively more attractive.

Nuclear weapons and deterrence[edit]

In 1966 Schelling[3] is prescriptive in outlining the impact of the development of nuclear weapons in the analysis of military power and deterrence. In his 1966 analysis, before the widespread use of assured second strike capability, or immediate reprisal, in the form of SSBN submarines, Schelling argues that nuclear weapons give nations the potential to not only destroy their enemies but humanity itself without drawing immediate reprisal because of the lack of a conceivable defense system and the speed with which nuclear weapons can be deployed. A nation's credible threat of such severe damage empowers their deterrence policies and fuels political coercion and military deadlock, which in turn can produce proxy warfare.

Historical analysis of nuclear weapons deterrent capabilities has led modern researchers to the concept of the stability-instability paradox, whereby nuclear weapons confer large scale stability between nuclear weapon states, as in over 60 years none have engaged in large direct warfare due primarily to nuclear weapons deterrence capabilities, but instead are forced into pursuing political aims by military means in the form of comparatively smaller scale acts of instability, such as proxy wars and minor conflicts.

Stages of the US policy of deterrence[edit]

The US policy of deterrence during the Cold War underwent significant variations.

Containment[edit]

The early stages of the Cold War were generally characterized by containment of communism, an aggressive stance on behalf of the US especially on developing nations under its sphere of influence. This period was characterized by numerous proxy wars throughout most of the globe, particularly Africa, Asia, Central America, and South America. A notable such conflict was the Korean War. George F. Kennan, who is taken to be the founder of this ideology in his Long Telegram, asserted that he never advocated military intervention, merely economic support; and that his ideas were misinterpreted when espoused by the general public.

Détente[edit]

With the U.S. drawdown from Vietnam, the normalization of U.S. relations with China, and the Sino-Soviet Split, the policy of Containment was abandoned and a new policy of détente was established, whereby peaceful coexistence was sought between the United States and the Soviet Union. Although all factors listed above contributed to this shift, the most important factor was probably the rough parity achieved in stockpiling nuclear weapons with the clear capability of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD). Therefore, the period of détente was characterized by a general reduction in the tension between the Soviet Union and the United States and a thawing of the Cold War, lasting from the late 1960s until the start of the 1980s. The doctrine of mutual nuclear deterrence characterized relations between the United States and the Soviet Union during this period, and relations with Russia until the onset of the New Cold War in the early 2010s. Since then, the relations have been less clear.

Cold War Museum Website

Reagan era[edit]

A third shift occurred with President Ronald Reagan's arms build-up during the 1980s. Reagan attempted to justify this policy in part due to concerns of growing Soviet influence in Latin America and the new republic of Iran, established after the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Similar to the old policy of containment, the United States funded several proxy wars, including support for Saddam Hussein of Iraq during the Iran–Iraq War, support for the mujahideen in Afghanistan, who were fighting for independence from the Soviet Union, and several anti-communist movements in Latin America such as the overthrow of the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. The funding of the Contras in Nicaragua led to the Iran-Contra Affair, while overt support led to a ruling from the International Court of Justice against the United States in Nicaragua v. United States.

While the army was dealing with the breakup of the Soviet Union and the spread of nuclear technology to other nations beyond the United States and Russia, the concept of deterrence took on a broader multinational dimension. The U.S. policy on post–Cold War deterrence was outlined in 1995 in a document called 'Essentials of Post–Cold War Deterrence'.[13] This document explains that while relations with Russia continue to follow the traditional characteristics of Mutual Nuclear Deterrence, due to both nations continuing MAD, U.S. policy of deterrence towards nations with minor nuclear capabilities should ensure through threats of immense retaliation (or even preemptive action) that they do not threaten the United States, its interests, or allies. The document explains that such threats must also be used to ensure that nations without nuclear technology refrain from developing nuclear weapons and that a universal ban precludes any nation from maintaining chemical or biological weapons. The current tensions with Iran and North Korea over their nuclear programs are due in part to the continuation of this policy of deterrence.

Modern Deterrence[edit]

Game Theory Cold War

Modern Deterrence is the application of deterrence theory to non-nuclear and post-nuclear challenges, including hybrid warfare.[14] As with nuclear deterrence, the aim of modern deterrence is to 'dissuade an adversary from taking aggressive action by persuading that actor that the costs would outweigh the potential gains.'[15] However, the unattributable nature of some new forms of attacks, including propaganda and cyber attacks, and the fact that they may be below the threshold of an armed response pose a particular challenge for deterrence. CSIS have concluded that modern deterrence is made most effective at reducing the threat of non-nuclear attacks by:

- Establishing norms of behavior;

- Tailoring deterrence threats to individual actors;

- Adopting an all of government and society response; and

- Building credibility with adversaries, for example by always following through on threats.[15]

Criticism[edit]

Deterrence theory is criticized for its assumptions about opponent rationales.

First, it is argued that suicidal or psychotic opponents may not be deterred by either forms of deterrence.[16] Second, if two enemy states both possess nuclear weapons, Country X may try to gain a first-strike advantage by suddenly launching weapons at Country Y, with a view to destroying its enemy's nuclear launch silos thereby rendering Country Y incapable of a response. Third, diplomatic misunderstandings and/or opposing political ideologies may lead to escalating mutual perceptions of threat, and a subsequent arms race that elevates the risk of actual war, a scenario illustrated in the movies WarGames (1983) and Dr. Strangelove (1964). An arms race is inefficient in its optimal output, as all countries involved expend resources on armaments that would not have been created if the others had not expended resources, a form of positive feedback. Fourth, escalation of perceived threat can make it easier for certain measures to be inflicted on a population by its government, such as restrictions on civil liberties, the creation of a military–industrial complex, and military expenditures resulting in higher taxes and increasing budget deficits.

In recent years, many mainstream politicians, academic analysts, and retired military leaders have also criticized deterrence and advocated nuclear disarmament. Sam Nunn, William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and George Shultz have all called upon governments to embrace the vision of a world free of nuclear weapons, and in three Wall Street Journal op-eds proposed an ambitious program of urgent steps to that end. The four have created the Nuclear Security Project to advance this agenda. Organisations such as Global Zero, an international non-partisan group of 300 world leaders dedicated to achieving nuclear disarmament, have also been established.[17] In 2010, the four were featured in a documentary film entitled Nuclear Tipping Point. The film is a visual and historical depiction of the ideas laid forth in the Wall Street Journal op-eds and reinforces their commitment to a world without nuclear weapons and the steps that can be taken to reach that goal.[18][19]

Former Secretary Kissinger puts the new danger, which cannot be addressed by deterrence, this way: 'The classical notion of deterrence was that there was some consequences before which aggressors and evildoers would recoil. In a world of suicide bombers, that calculation doesn't operate in any comparable way.'[20] Shultz has said, 'If you think of the people who are doing suicide attacks, and people like that get a nuclear weapon, they are almost by definition not deterrable'.[21]

Game Theory And The Humanities

As opposed to the extreme mutually assured destruction form of deterrence, the concept of minimum deterrence in which a state possesses no more nuclear weapons than is necessary to deter an adversary from attacking is presently the most common form of deterrence practiced by nuclear weapon states, such as China, India, Pakistan, Britain, and France.[22] Pursuing minimal deterrence during arms negotiations between United States and Russia allows each state to make nuclear stockpile reductions without the state becoming vulnerable, however it has been noted that there comes a point where further reductions may be undesirable, once minimal deterrence is reached, as further reductions beyond this point increase a state's vulnerability and provide an incentive for an adversary to secretly expand its nuclear arsenal.[23]

'Senior European statesmen and women' called for further action in addressing problems of nuclear weapons proliferation in 2010. They said: 'Nuclear deterrence is a far less persuasive strategic response to a world of potential regional nuclear arms races and nuclear terrorism than it was to the cold war'.[6]

Paul Virilio has criticized nuclear deterrence as anachronistic in the age of information warfare since disinformation and kompromat are the current threats to suggestible populations. The wound inflicted on unsuspecting populations he calls an 'integral accident':

- The first deterrence, nuclear deterrence, is presently being superseded by the second deterrence: a type of deterrence based on what I call 'the information bomb' associated with the new weaponry of information and communications technologies. Thus, in the very near future, and I stress this important point, it will no longer be war that is the continuation of politics by other means, it will be what I have dubbed 'the integral accident' that is the continuation of politics by other means.[24]

Former deputy defense secretary and strategic arms treaty negotiator Paul Nitze stated in a Washington Post op-ed in 1994 that nuclear weapons were obsolete in the 'new world disorder' following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and advocated reliance on precision guided munitions to secure a permanent military advantage over future adversaries.[25]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Definition of deterrence from the Dictionary of Modern Strategy and Tactics by Michael Keane: 'The prevention or inhibition of action brought about by fear of the consequences. Deterrence is a state of mind brought about by the existence of a credible threat of unacceptable counteraction. It assumes and requires rational decision makers.'

References[edit]

Cold War Museum Ohio

- ^https://www.britannica.com/topic/deterrence-political-and-military-strategy

- ^Brodie, Bernard (1959), '8', 'The Anatomy of Deterrence' as found in Strategy in the Missile Age, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 264–304

- ^ abcSince the consequence of a breakdown of the nuclear deterrence strategy is so catastrophic for human civilisation, it is reasonableness to employ the strategy only if the chance of breakdown is zero.Schelling, T. C. (1966), '2', The Diplomacy of Violence, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 1–34

- ^Zagare, Frank C. (2004), 'Reconciling Rationality with Deterrence: A Re-examination of the Logical Foundations of Deterrence Theory', Journal of Theoretical Politics, 16 (2): 107–141, CiteSeerX10.1.1.335.7353, doi:10.1177/0951629804041117

- ^ ab'Nuclear endgame: The growing appeal of zero'. The Economist. June 16, 2011.

- ^ abKåre Willoch, Kjell Magne Bondevik, Gro Harlem Brundtland, Thorvald Stoltenberg, Wlodzimierz Cimoszewicz, Ruud Lubbers, Jean-Luc Dehaene, Guy Verhofstadt; et al. (14 April 2010). 'Nuclear progress, but dangers ahead'. The Guardian.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^See, for example, Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. and ed. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989)

- ^Iain King (February 12, 2019). 'What do Cognitive Biases mean for Deterrence?'. The Strategy Bridge.

- ^ abcdeHuth, P. K. (1999), 'Deterrence and International Conflict: Empirical Findings and Theoretical Debate', Annual Review of Political Science, 2: 25–48, doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.25

- ^ abcdJentleson, B.A.; Whytock, C.A. (2005), 'Who Won Libya', International Security, 30 (3): 47–86, doi:10.1162/isec.2005.30.3.47

- ^George, A (1991), 'The General Theory and Logic of Coercive Diplomacy', Forceful Persuasion: Coercive Diplomacy as an Alternative to War, Washington, D.C: United States Institute of Peace Press, pp. 3–14

- ^Jervis, Robert (1982). 'Deterrence and Perception'. International Security. 7 (3): 3–30. doi:10.2307/2538549. JSTOR2538549.

- ^'The Nautilus Institute Nuclear Strategy Project: US FOIA Documents'. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008.

- ^RUSI Modern Deterrence program

- ^ abCenter for Strategic and International Studies video on Modern Deterrence

- ^Towle, Philip (2000). 'Cold War'. In Charles Townshend (ed.). The Oxford History of Modern War. New York, US: Oxford University Press. p. 164. ISBN978-0-19-285373-8.

- ^Maclin, Beth (2008-10-20) 'A Nuclear weapon-free world is possible, Nunn says', Belfer Center, Harvard University. Retrieved on 2008-10-21.

- ^'The Growing Appeal of Zero'. The Economist. June 18, 2011. p. 66.

- ^'Documentary Advances Nuclear Free Movement'. NPR. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ^Ben Goddard (2010-01-27). 'Cold Warriors say no nukes'. The Hill.

- ^Hugh Gusterson (30 March 2012). 'The new abolitionists'. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- ^Kristensen, Hans M, Robert S Norris, and Ivan Oelrich. 'From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence: A New Nuclear Policy on the Path Toward Eliminating Nuclear Weapons.' Federation of American Scientists. April 2009. Accessed July 31, 2010.

- ^Nalebuff, Barry. 'Minimal Nuclear Deterrence.' Journal of Conflict Resolution 32, no. 3 (September 1988): pg 424.

- ^John Armitage (October 18, 2000) The Kosovo War Took Place In Orbital Space: Paul Virilio in Conversation. , Ctheory

- ^Nitze, Paul. 'IS IT TIME TO JUNK OUR NUKES? THE NEW WORLD DISORDER MAKES THEM OBSOLETE'. washingtonpost dot com. WP Company LLC. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

Game Theory And The Evolution Of Signaling

- 'U.S. Department of Defense's Deterrence Operations Joint Operating Concept'. Archived from the original(Word) on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

Further reading[edit]

- Schultz, George P. and Goodby, James E. The War that Must Never be Fought, Hoover Press, ISBN978-0-8179-1845-3, 2015.

- Freedman, Lawrence. 2004. Deterrence. New York: Polity Press.

- Jervis, Robert, Richard N. Lebow and Janice G. Stein. 1985. Psychology and Deterrence. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 270 pp.

- Morgan, Patrick. 2003. Deterrence Now. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- T.V. Paul, Patrick M. Morgan, James J. Wirtz, Complex Deterrence: Strategy In the Global Age (University of Chicago Press, 2009) ISBN978-0-226-65002-9.

- Garcia Covarrubias, Jaime. 'The Significance of Conventional Deterrence in Latin America', March–April 2004.

- Waltz, Kenneth N. 'Nuclear Myths and Political Realities'. The American Political Science Review. Vol. 84, No. 3 (Sep, 1990), pp. 731–746.

External links[edit]

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Survey research and design in psychology/Tutorials/Multiple linear regression/Exercises/Deterrence theory |

- Nuclear Deterrence Theory and Nuclear Deterrence Myth, streaming video of a lecture by Professor John Vasquez, Program in Arms Control, Disarmament, and International Security (ACDIS), University of Illinois, September 17, 2009.

- Deterrence Today – Roles, Challenges, and Responses, analysis by Lewis A. Dunn, IFRI Proliferation Papers n° 19, 2007

- Revisiting Nuclear Deterrence Theory by Donald C. Whitmore – March 1, 1998

- Nuclear Deterrence, Missile Defenses, and Global Instability by David Krieger, April 2001

- Maintaining Nuclear Deterrence in the 21st Century by the Senate Republican Policy Committee

- Nuclear Files.org Description and analysis of the nuclear deterrence theory

- Nuclear Files.org Speech by US General Lee Butler in 1998 on the Risks of Nuclear Deterrence

- Nuclear Files.org Speech by Sir Joseph Rotblat, Nobel Peace Laureate, on the Ethical Dimensions of Deterrence

- The Universal Formula for Successful Deterrence by Charles Sutherland, 2007. A predictive tool for deterrence strategies.

- Will the Eagle strangle the Dragon?, Analysis of how the Chinese nuclear deterrence is altered by the U.S. BMD system, Trends East Asia, No. 20, February 2008.

- When is Deterrence Necessary? Gauging Adversary Intent by Gary Schaub,Jr., Strategic Studies Quarterly 3, 4 (Winter 2009)